When Fausto Coppi won Paris-Roubaix

Fausto Coppi is a name that still resonates in cycling today, even though his era was the 1940s and early 1950s. He was at his best in the mountains, or in a time trial, but Coppi could win anywhere, as he proved in 1950.

Words: Chris Sidwells.

Photos: Offside and Cycling Legends.

“One day, in a cloud of golden dust, I saw the sun riding a bicycle between Grosseto and Follonica.” That is how top journalist and former racer Jean Bobet described being caught and passed by Fausto Coppi in a time trial stage of the 1953 Tour of Italy

Okay, journalistic style leant towards hyperbole back then, but exaggeration was justified in before TV to convey the majesty of Coppi in cycling motion. He was a superb cyclist, a natural who looked ungainly off his bike but like a God on it. He pedalled away from rivals like he was in another dimension where physical forces didn’t exist. He appeared to float on his bike, even over the roughest surfaces, as he proved in the roughest race of all; Paris-Roubaix.

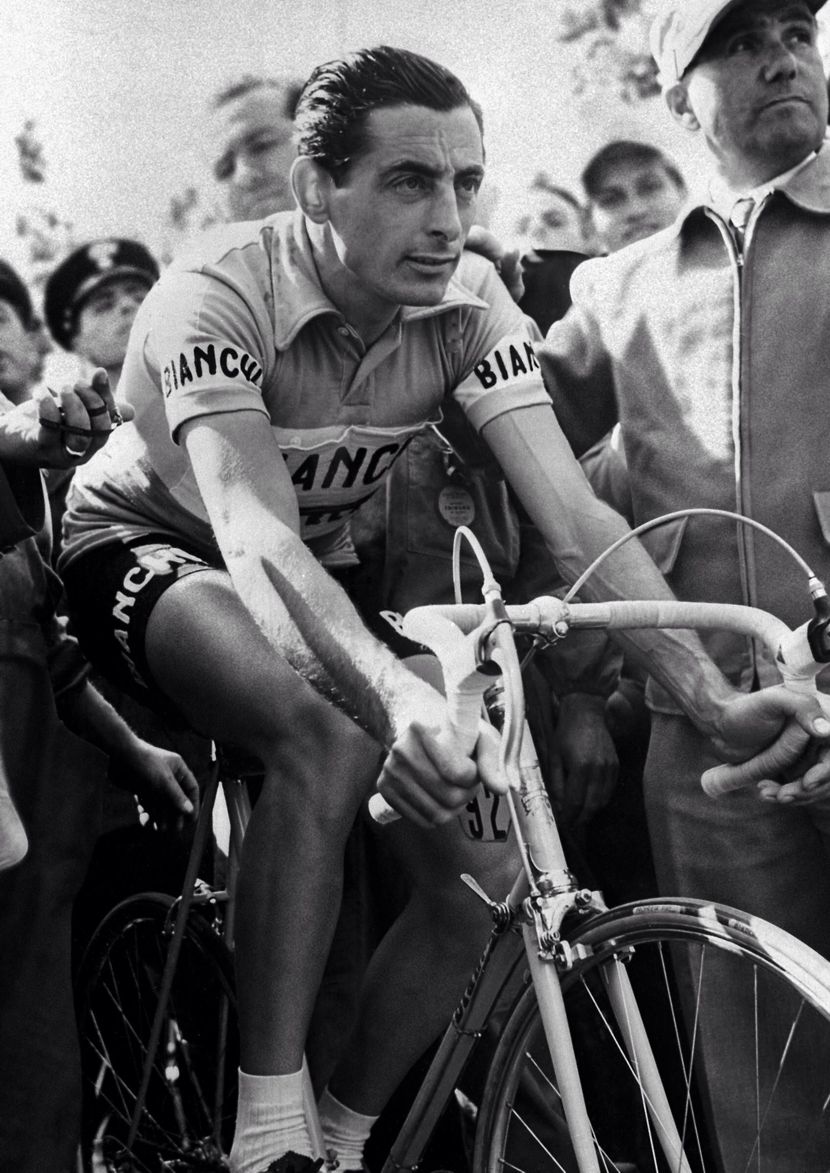

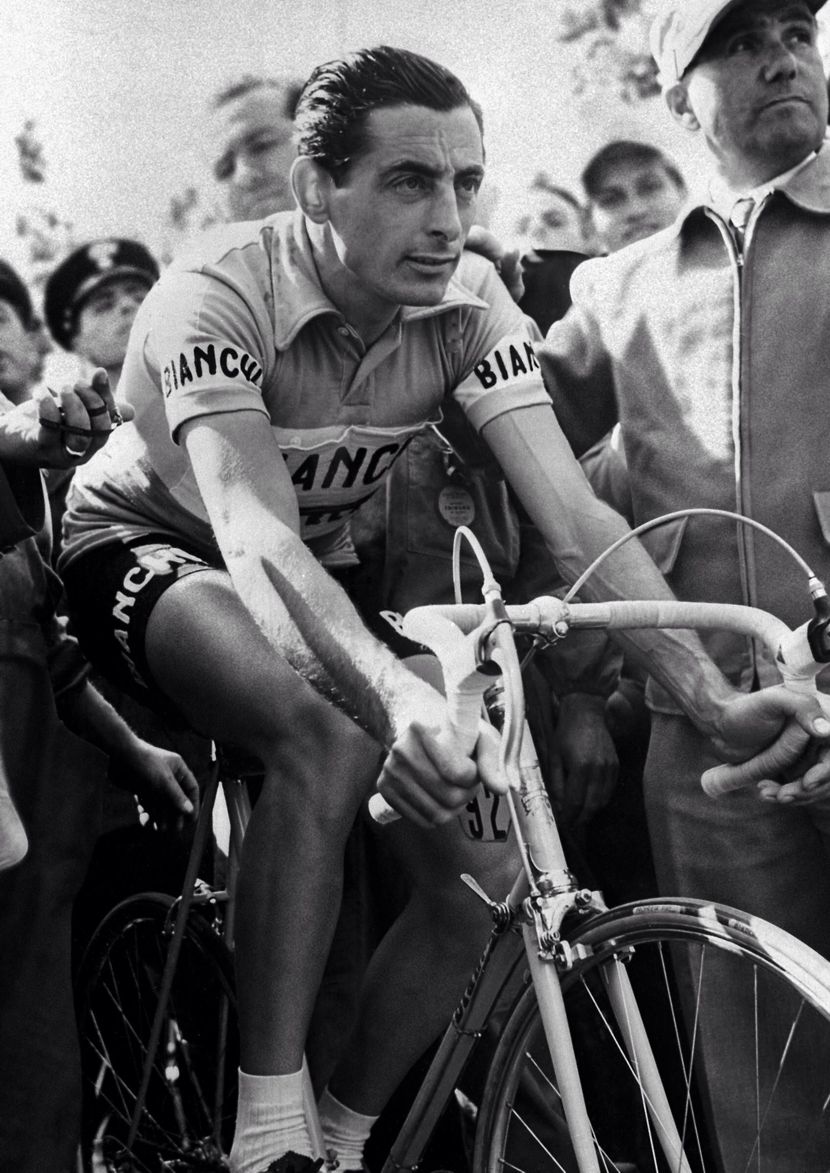

Fausto Coppi at the start of the Grosetto to Follonica time trial stage of the 1953 Giro d'Italia

Coppi won Paris-Roubaix in 1950, he was second in 1952 and second again in 1955, and his brother Serse won the race in a controversial finish. Fausto Coppi won Paris-Roubaix for the same reason he won everything; he was a master of cycling, a master of almost every aspect of the sport, a world champion on the track, an hour record holder, a multi-Grand Tour winner, a world road race champion and a multiple Classics winner.

In the whole history of cycling only Eddy Merckx rivals Fausto Coppi, and even then their careers require qualification before comparison. Merckx is well ahead on total victories, but he never had the career breaks Coppi did, including a World War as well as lots of time out for broken bones. Where they are equals, though, is in the manner in which they won. Their victories were decisive, total, transcending sport; a Coppi or Merckx victory was a thing of beauty.

When Coppi attacked it seemed like time stood still. He rarely grimaced, he never pulled and pushed at his bike like Merckx did. Most of time he didn’t even get out of the saddle to attack, Coppi’s legs would simply snap into a faster cadence and he was gone. And once he went, that was it. There was a period in Coppi’s career, and it lasted months, when he was never caught once he’d made his attack.

Coppi leads on Alpe d'Huez in 1952

Coppi came out of the Second World War reduced physically but alive and uninjured. Compared to many he had a comfortable time while held by the allies as a prisoner of war. Of course he couldn’t train, but it didn’t take long for him to get fit and resume his career trajectory after his release.

Coppi won Milan-San Remo in 1946, 1948 and in 1949, and did the Italian monument double of San Remo and Lombardy in those last two years. He was world pursuit champion in 1947. He won the 1947 Giro d’Italia then he won again in 1949, along with the Tour de France that same year. And in those Grand Tours, Coppi won stages and the King of the Mountains titles as well as the overall.

He lined up for the 1950 Paris Roubaix as the world number one, but without a great deal of experience in the cobbled races of the north. If you compared what Coppi had won so far to boxing, his successes were fought under Lonsdale Rules and Paris-Roubaix is a pub brawl. Then as now Belgians won on the cobbles, seven of the previous ten editions of Paris-Roubaix had fallen to the tough street-fighters of Flanders. They were stocky muscular men, not long-legged aesthetes like Fausto Coppi.

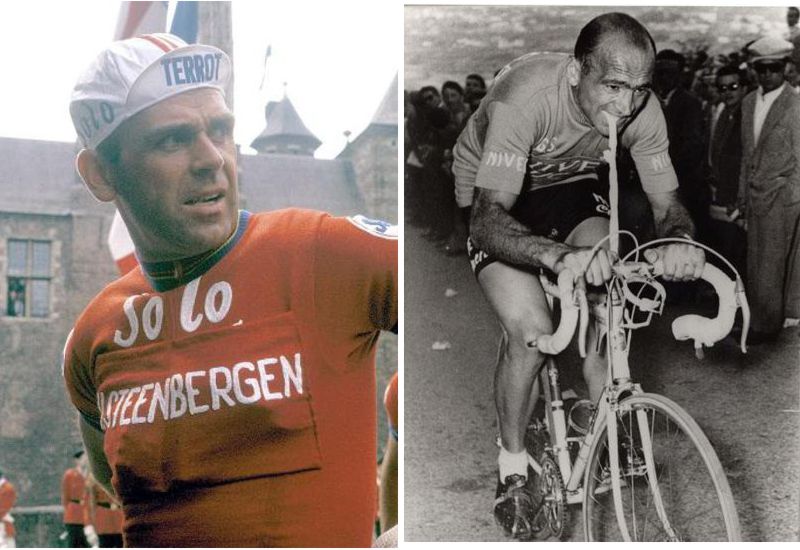

The race favourites were Rik Van Steenbergen and an Italian, Forenzi Magni, who looked more like a Mafia enforcer than a professional cyclist. Magni had won the Tour of Flanders three years in a row, and is still the only man ever to have done that. He was as tough as teak. He broke his collar bone in the 1956 Giro d’Italia, but wouldn’t drop out. He couldn’t pull with the arm on his broken side so when the road climbed Magni compensated by pulling on his handlebars with a sling of handlebar tape held between his teeth.

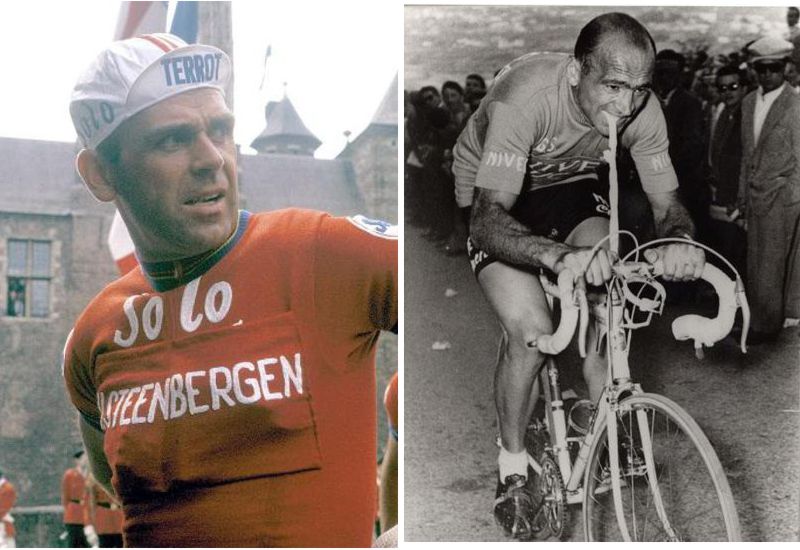

Rik Van Steenbergen Fiorenzo Magni

Rik Van Steenbergen Fiorenzo Magni

And the weather didn’t help Coppi, who had less fat on him than a butcher’s pencil. Commenting once on his younger rival the great Italian Tour and Giro winner Gino Bartali said; “Coppi looks like a skinned cat.” But wearing his national champion’s Tricolor jersey, short sleeves with no arm or leg warmers, Coppi looked unconcerned as he set off from Paris in heavy cold rain.

Paris-Roubaix didn’t have to hunt out cobbles in the 1950s, like it does today, because after crossing the undulations of Picardie and once they got into the Nord-Pas de Calais region, even the main roads were cobbled. The Picardie hills saw a flurry of early attacks, but Coppi rode to plan, saving his attack for the cobbled tramline madness in the city of Arras.

Coppi was a marginal gains man and he had his mechanic Pinalla di Grande build a special bike for Paris-Roubaix equipped with a single 52-tooth chainring and the old Cambio Corsa derailleur gears.

The Cambio Corsa was a difficult contraption to operate, involving reaching down to the lower part of the bike’s drive-side seat-stay to operate a rod and lever with a little fork on the end to make each gear shift. Cable operated derailleurs were available, and they were easier to use, but Coppi thought that such a shifter might not be up to the battering it would get in the Hell of the North, where at least a Cambio Corsa gear shift stayed put once it was in. Anyway, Paris-Roubaix is mostly flat, so three gears, because that’s all Coppi had, was no great handicap.

The Cambio Corsa gear mechanism on Coppi's Bianchi bike

His team, as ever, was entirely dedicated to him. He picked some of his best and most trusted gregari for the race; Oreste Conte, Bruno Pasquini, Fiorenzo Crippa, Ettore Milano, Sandrino Carrea, and Coppi’s brother Serse, who had shared victory in the 1949 Paris-Roubaix. And that was a story in itself.

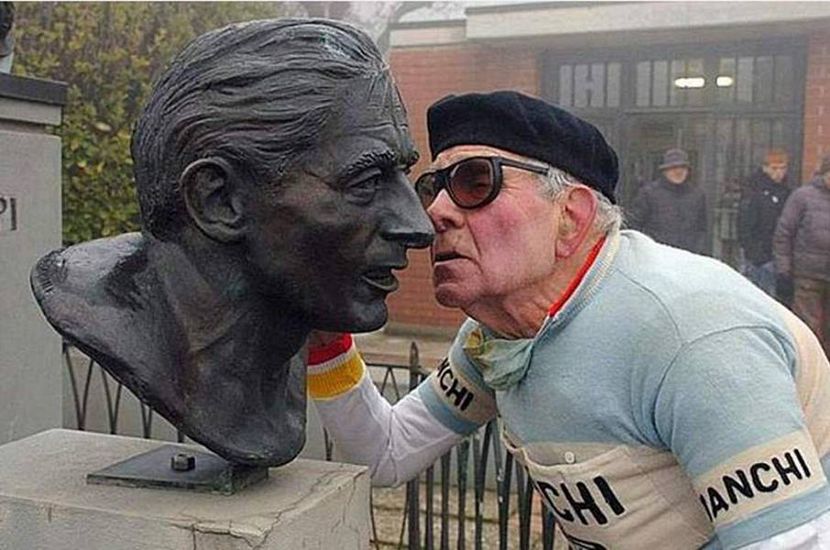

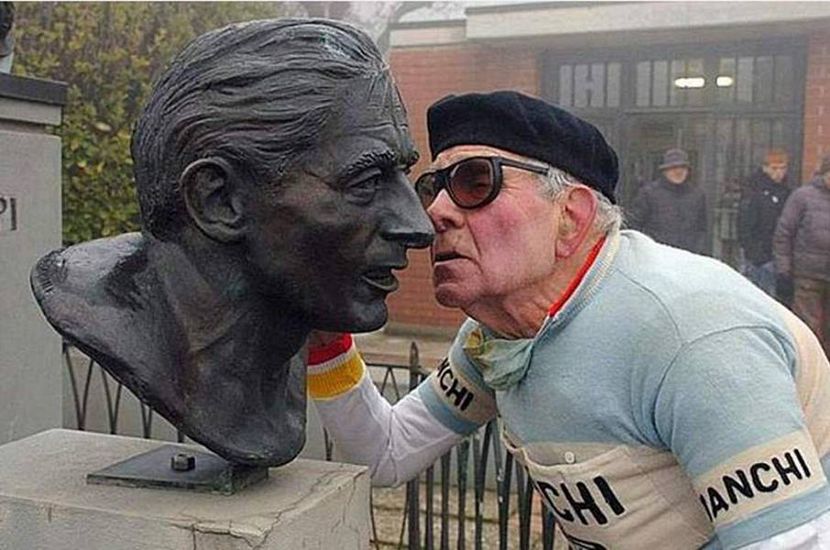

Devotion to Coppi is for life, Valeriano Flasini joined the Binachi team in 1951

Andre Mahé crossed the line first in 1949. Mahé and two other riders, Jacques Moujica and Frans Leeman entered the park where the Roubaix Velodrome is situated together, but they were misdirected and couldn’t get into the Velodrome. The three riders panicked, not unnaturally, and Moujica damaged his bike trying to climb into the stadium. Mahé found a back entrance, got through it, and crossed the line first, just ahead of a group led by Serse Coppi.

Mahé was declared the winner, but when Serse and Fausto heard about how the race ended they protested, claiming that since Mahé hadn’t completed the full official route but Serse had, then Serse should be the winner. Eventually the race judges agreed and Serse Coppi was given the victory. But five days later the French Cycling Federation protested and the decision was reversed, only for the Italian Federation to protest and get it switched back again. Eventually it took two meetings of the UCI to fix the record books, Mahé and Coppi were made joint winners, with no second place awarded, and Frans Leeman given third.

Coppi on the attacks coming out of Arras

Two riders were clear when the main field hit Arras; Gino Sciardis and Maurice Diot, then Coppi accelerated across the gap to join them. He injected new pace into the break, Sciardis was quickly dropped and Diot was told by his manager Antonin Magne not to work. His team mate and race favourite Rik Van Steenbergen was chasing the group. Not that Diot had any choice but to cling to Coppi’s rear wheel.

Catching then dropping Diot

But Van Steenbergen got nowhere near, and with 45 kilometres to go Coppi accelerated again. Diot was dropped and Coppi sailed serenely over the final 40 kilometres of cobbles in exactly one hour to win by 2 minutes and 45 seconds from Diot. He was 5 minutes 24 ahead of third-placed Fiorenzo Magni, who dropped the Van Steenbergen group. The Belgian pre-race favourite ended up over seven minutes behind Coppi.

Coppi stayed in the north, and a few days after Paris-Roubaix he won La Flèche-Wallonne in a 100-kilometre lone break. Only an accident could have stopped him dominating cycling in 1950, as he had increasingly dominated it since the War. Sure enough that accident happened in the Giro d’Italia when Coppi suffered a triple fracture to his pelvis.

It took almost all the rest of the season for him to return to anything like fitness, and a diminished Coppi took third in the Tour of Lombardy and was second with Serse in the season-ending Baracchi Trophy time trial. It was a bad end to a year that promised so much, but an even bigger tragedy lurked just around the corner for the Coppi family.

It happened in 1951 Giro del Piemonte. Coppi hadn’t gone so well in the race, so his brother Serse stayed with him to encourage him, but in the final kilometres he let his front wheel slip into the Turin tramlines. Serse and two others crashed, but only Serse didn’t continue. Instead he rode to the team’s hotel and appeared okay, but later the same day he collapsed and was taken to hospital where concussion was diagnosed. His condition worsened and it was decided to operate, but Serse died in his brother’s arms before they could.

Coppi’s life was like that; glorious triumphs and terrible tragedies. He suffered countless crashes, and almost always broke bones in them. His body, perfectly adapted to cycling seemed ill adapted to anything else. It lacked the robustness to carry his talent. His private life was a mess of emotion too. Coppi fell in love with a married woman when he was married too. The couple eventually made a life together and had a son; Faustino.

But when it finally looked like he had found happiness Coppi contracted Malaria during a late 1959 racing trip to Africa. It was misdiagnosed at first and by the time the correct diagnosis was arrived at, it was too late. Fausto Coppi died on January 2nd, 1960. He was just 40 years old.

Okay, journalistic style leant towards hyperbole back then, but exaggeration was justified in before TV to convey the majesty of Coppi in cycling motion. He was a superb cyclist, a natural who looked ungainly off his bike but like a God on it. He pedalled away from rivals like he was in another dimension where physical forces didn’t exist. He appeared to float on his bike, even over the roughest surfaces, as he proved in the roughest race of all; Paris-Roubaix.

Fausto Coppi at the start of the Grosetto to Follonica time trial stage of the 1953 Giro d'Italia

Coppi won Paris-Roubaix in 1950, he was second in 1952 and second again in 1955, and his brother Serse won the race in a controversial finish. Fausto Coppi won Paris-Roubaix for the same reason he won everything; he was a master of cycling, a master of almost every aspect of the sport, a world champion on the track, an hour record holder, a multi-Grand Tour winner, a world road race champion and a multiple Classics winner.

In the whole history of cycling only Eddy Merckx rivals Fausto Coppi, and even then their careers require qualification before comparison. Merckx is well ahead on total victories, but he never had the career breaks Coppi did, including a World War as well as lots of time out for broken bones. Where they are equals, though, is in the manner in which they won. Their victories were decisive, total, transcending sport; a Coppi or Merckx victory was a thing of beauty.

When Coppi attacked it seemed like time stood still. He rarely grimaced, he never pulled and pushed at his bike like Merckx did. Most of time he didn’t even get out of the saddle to attack, Coppi’s legs would simply snap into a faster cadence and he was gone. And once he went, that was it. There was a period in Coppi’s career, and it lasted months, when he was never caught once he’d made his attack.

Coppi leads on Alpe d'Huez in 1952

Coppi came out of the Second World War reduced physically but alive and uninjured. Compared to many he had a comfortable time while held by the allies as a prisoner of war. Of course he couldn’t train, but it didn’t take long for him to get fit and resume his career trajectory after his release.

Coppi won Milan-San Remo in 1946, 1948 and in 1949, and did the Italian monument double of San Remo and Lombardy in those last two years. He was world pursuit champion in 1947. He won the 1947 Giro d’Italia then he won again in 1949, along with the Tour de France that same year. And in those Grand Tours, Coppi won stages and the King of the Mountains titles as well as the overall.

He lined up for the 1950 Paris Roubaix as the world number one, but without a great deal of experience in the cobbled races of the north. If you compared what Coppi had won so far to boxing, his successes were fought under Lonsdale Rules and Paris-Roubaix is a pub brawl. Then as now Belgians won on the cobbles, seven of the previous ten editions of Paris-Roubaix had fallen to the tough street-fighters of Flanders. They were stocky muscular men, not long-legged aesthetes like Fausto Coppi.

The race favourites were Rik Van Steenbergen and an Italian, Forenzi Magni, who looked more like a Mafia enforcer than a professional cyclist. Magni had won the Tour of Flanders three years in a row, and is still the only man ever to have done that. He was as tough as teak. He broke his collar bone in the 1956 Giro d’Italia, but wouldn’t drop out. He couldn’t pull with the arm on his broken side so when the road climbed Magni compensated by pulling on his handlebars with a sling of handlebar tape held between his teeth.

Rik Van Steenbergen Fiorenzo Magni

Rik Van Steenbergen Fiorenzo MagniAnd the weather didn’t help Coppi, who had less fat on him than a butcher’s pencil. Commenting once on his younger rival the great Italian Tour and Giro winner Gino Bartali said; “Coppi looks like a skinned cat.” But wearing his national champion’s Tricolor jersey, short sleeves with no arm or leg warmers, Coppi looked unconcerned as he set off from Paris in heavy cold rain.

Paris-Roubaix didn’t have to hunt out cobbles in the 1950s, like it does today, because after crossing the undulations of Picardie and once they got into the Nord-Pas de Calais region, even the main roads were cobbled. The Picardie hills saw a flurry of early attacks, but Coppi rode to plan, saving his attack for the cobbled tramline madness in the city of Arras.

Coppi was a marginal gains man and he had his mechanic Pinalla di Grande build a special bike for Paris-Roubaix equipped with a single 52-tooth chainring and the old Cambio Corsa derailleur gears.

The Cambio Corsa was a difficult contraption to operate, involving reaching down to the lower part of the bike’s drive-side seat-stay to operate a rod and lever with a little fork on the end to make each gear shift. Cable operated derailleurs were available, and they were easier to use, but Coppi thought that such a shifter might not be up to the battering it would get in the Hell of the North, where at least a Cambio Corsa gear shift stayed put once it was in. Anyway, Paris-Roubaix is mostly flat, so three gears, because that’s all Coppi had, was no great handicap.

The Cambio Corsa gear mechanism on Coppi's Bianchi bike

His team, as ever, was entirely dedicated to him. He picked some of his best and most trusted gregari for the race; Oreste Conte, Bruno Pasquini, Fiorenzo Crippa, Ettore Milano, Sandrino Carrea, and Coppi’s brother Serse, who had shared victory in the 1949 Paris-Roubaix. And that was a story in itself.

Devotion to Coppi is for life, Valeriano Flasini joined the Binachi team in 1951

Andre Mahé crossed the line first in 1949. Mahé and two other riders, Jacques Moujica and Frans Leeman entered the park where the Roubaix Velodrome is situated together, but they were misdirected and couldn’t get into the Velodrome. The three riders panicked, not unnaturally, and Moujica damaged his bike trying to climb into the stadium. Mahé found a back entrance, got through it, and crossed the line first, just ahead of a group led by Serse Coppi.

Mahé was declared the winner, but when Serse and Fausto heard about how the race ended they protested, claiming that since Mahé hadn’t completed the full official route but Serse had, then Serse should be the winner. Eventually the race judges agreed and Serse Coppi was given the victory. But five days later the French Cycling Federation protested and the decision was reversed, only for the Italian Federation to protest and get it switched back again. Eventually it took two meetings of the UCI to fix the record books, Mahé and Coppi were made joint winners, with no second place awarded, and Frans Leeman given third.

Coppi on the attacks coming out of Arras

Two riders were clear when the main field hit Arras; Gino Sciardis and Maurice Diot, then Coppi accelerated across the gap to join them. He injected new pace into the break, Sciardis was quickly dropped and Diot was told by his manager Antonin Magne not to work. His team mate and race favourite Rik Van Steenbergen was chasing the group. Not that Diot had any choice but to cling to Coppi’s rear wheel.

Catching then dropping Diot

But Van Steenbergen got nowhere near, and with 45 kilometres to go Coppi accelerated again. Diot was dropped and Coppi sailed serenely over the final 40 kilometres of cobbles in exactly one hour to win by 2 minutes and 45 seconds from Diot. He was 5 minutes 24 ahead of third-placed Fiorenzo Magni, who dropped the Van Steenbergen group. The Belgian pre-race favourite ended up over seven minutes behind Coppi.

Coppi stayed in the north, and a few days after Paris-Roubaix he won La Flèche-Wallonne in a 100-kilometre lone break. Only an accident could have stopped him dominating cycling in 1950, as he had increasingly dominated it since the War. Sure enough that accident happened in the Giro d’Italia when Coppi suffered a triple fracture to his pelvis.

It took almost all the rest of the season for him to return to anything like fitness, and a diminished Coppi took third in the Tour of Lombardy and was second with Serse in the season-ending Baracchi Trophy time trial. It was a bad end to a year that promised so much, but an even bigger tragedy lurked just around the corner for the Coppi family.

It happened in 1951 Giro del Piemonte. Coppi hadn’t gone so well in the race, so his brother Serse stayed with him to encourage him, but in the final kilometres he let his front wheel slip into the Turin tramlines. Serse and two others crashed, but only Serse didn’t continue. Instead he rode to the team’s hotel and appeared okay, but later the same day he collapsed and was taken to hospital where concussion was diagnosed. His condition worsened and it was decided to operate, but Serse died in his brother’s arms before they could.

Coppi’s life was like that; glorious triumphs and terrible tragedies. He suffered countless crashes, and almost always broke bones in them. His body, perfectly adapted to cycling seemed ill adapted to anything else. It lacked the robustness to carry his talent. His private life was a mess of emotion too. Coppi fell in love with a married woman when he was married too. The couple eventually made a life together and had a son; Faustino.

But when it finally looked like he had found happiness Coppi contracted Malaria during a late 1959 racing trip to Africa. It was misdiagnosed at first and by the time the correct diagnosis was arrived at, it was too late. Fausto Coppi died on January 2nd, 1960. He was just 40 years old.