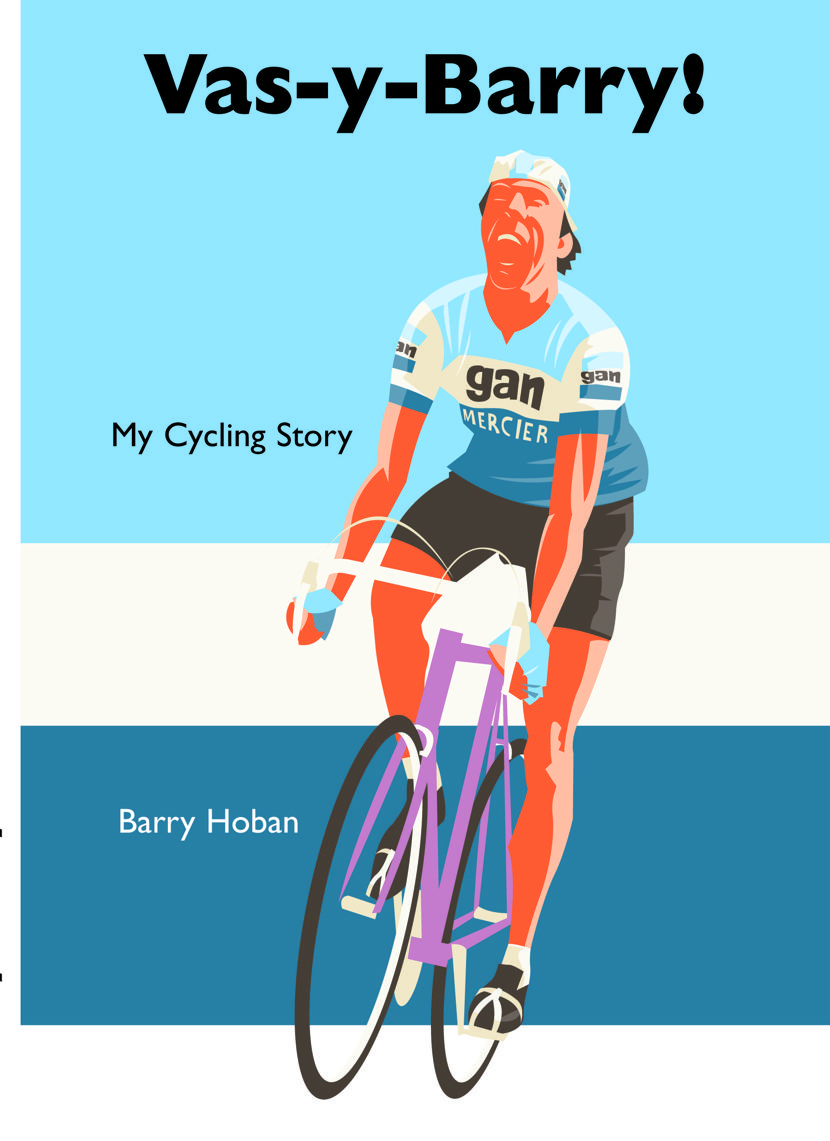

Hoban’s Classic

In this extract from his autobiography, Vas-y Barry, the only British winner of Ghent-Wevelgem Barry Hoban recounts how he won in 1974, beating Eddy Merckx and the cream of Belgian cycling to do it.

Words: Barry Hoban

The 1974 Gan-Mercier team was a really good team, and as well as experienced proven winners we had some good young riders in it. The Dutch riders Cees Bal and Gerrie Knetemann were very good, and Knetemann later became a great rider. It was very sad when he died in 2004, when he was still only 53 years old. We had their compatriot Joop Zoetemelk as well. We had Alain Santy, who was riding extremely well. And of course we had Raymond Poulidor, the ever-present Raymond Poulidor.

To kick things off properly we rode Paris-Nice, and we had an excellent race with Joop Zoetemelk winning it. One of the things we had in Gan-Mercier was riders who could dominate an uphill time trial. Eddy Merckx, even though he could dominate most things, he wasn’t the purest of climbers, and although no-one stood a chance against him in a flat time trial, anything around ten kilometres uphill was different. Paris-Nice ended with a nine kilometre time trial up the Col d’Eze, round the back of Nice. Joop Zoetemelk won it and took the race overall, Alain Santy was second and Raymond Poulidor was fifth, so that was a great start.

Joop Zoetemelk was at his best in 1974

I didn’t ride Milan-San Remo, so my next race was Semaine Catalane. We had sunshine, it’s often sunny around Barcelona, and the race had some serious climbing up into Andorra. Cees Bal took the lead on the first day; so wow, we were starting to get off to a flyer of a year. I finished third on a stage, so I was starting to tick. In the end the race came down to a stage that finished above Andorra, and it came down to a battle between Eddy Merckx and Joop Zoetemelk.

The finish was at the end of a long climb up to nearly 2000 metres, so just below the snow line. I didn’t see what happened, but I remember Joop telling me the story afterwards. He was going up side by side with Merckx and they were both on the 19 sprocket, then Merckx shifted into the 21. So Joop dropped down to the 17 and attacked. Bang, he dropped Merckx and rode away, and just annihilated him. Zoetemelk won the stage and the overall.

That was the real Joop Zoetemelk. Okay, he won the Tour de France in 1980 and lots of other races, but we never saw the real Joop Zoetemelk after 1974, the Joop Zoetemelk there could have been. He never achieved his full potential because later in 1974 Joop had a terrible accident during the Midi Libre. He was badly hurt, but complications set in that affected the rest of his career. One of the worst complications was that the infection he got after the crash affected his red blood cell production, and it was almost four years before his red cell count got back to normal. Those four years would have been the best of his career, because he was 27 in 1974 and just coming to his physical peak.

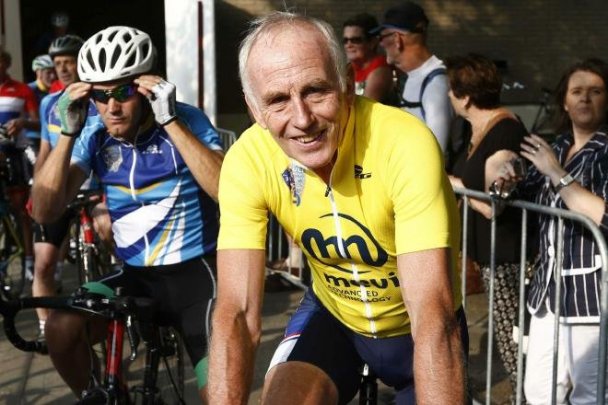

Zoetemelk, still riding after all those years

But we were on a roll at the start of 1974, and next up were the northern classics, the first of which was the Tour of Flanders. We were all good, we were all feeling great. I had a problem in the race and I missed the split, but we had riders in what was a big break with a lot of good riders in it.

It was the first year that the Tour of Flanders finished in Meerbeke, next to Ninove. So there was the Muur in Geraardsbergen, then the Bosberg, then coming off the Bosberg you had 10 kilometres, most of which was slightly downhill. Then you went right, then right again, then you went up a drag to the finish. And it was attack, after attack, after attack coming off the Bosberg. But then there was a lull and that’s when Cees Bal went, and Cees was a typical Dutch rider. He went off, found the gutter, put his head down and rode and rode, he rode as hard as he could. For a second nobody reacted, and that was all he needed, that hesitation, Cees won superbly. So, hey, we were still on a roll.

Cees Bal winning the 1974 Tour of Flanders

Next up was Ghent-Wevelgem, it was on the Wednesday between Flanders and Paris-Roubaix. Back then in Ghent-Wevelgem you zig-zagged your way to the coast, then you went down the coast and you turned inland near De Panne and came to the Hellingen, the hills; the Zwarterberg the Rodeberg, the Molenberg and the Kemmelberg. And Ghent-Wevelgem was well over 250 kilometres long back then, where in recent times they’ve cut the distance, which is a pity.

I remember Eddy Merckx saying in a newspaper; “I don’t know why a classic can’t be respected. Ghent-Wevelgem is a great classic, Flèche-Wallonne is a great classic, why knock 30 kilometres off them?” And he’s right, because those 30 kilometres are the difference between a hard race and a classic. If you’d have had Ghent-Wevelgem in my day with the distance they had recently, not now, they’ve built it up a bit, Patrick Sercu would have won it four of five times. That last hour was too much for Patrick. Also, in those days you had three circuits of the Zwarterberg the Molenberg, the Rodeberg and the Kemmelberg; three circuits. You went up the Kemmelberg three different ways too.

Patrick Sercu (inside) not only one of the best ever on the track, but also a very fast road sprinter

.

I loved that climb, it’s short, steep and nasty. The guys always put a 21 on for their biggest sprocket, but I fitted a 22, just to take a bit of the strain away. But one of the problems you had with the gears in those days was we didn’t have index gearing. We didn’t even have, what became the norm, the Simplex retro-friction leavers. We had Campagnolo friction gear levers, and they were notorious for moving when you put extra pressure on the pedals. And if the lever moved the chain jumped onto a smaller sprocket, usually about two down from what you were in; so bang, your legs would suddenly hit this much higher gear. I had that problem going up the Kemmelberg for the final time.

I was in the front group with Roger De Vlaeminck and Eddy Merckx. We were all side by side more or less, and I was riding on the brake lever hoods but sat down. You don’t get out of the saddle on the Kemmelberg, if you did your bike would bounce around all over the place. Then my gears started tick, tick, tick, ticking. The lever had moved and the chain was going to jump out of the 22. I took my hand off the hoods and I pushed the gear back in. But then it happened again, and again, and every time I pushed the lever back I lost a bit of ground. In the end I went over the top of the Kemmelberg about 15 to 20 metres behind the De Vlaeminck, Godefroot and Merckx group, and they weren’t hanging about.

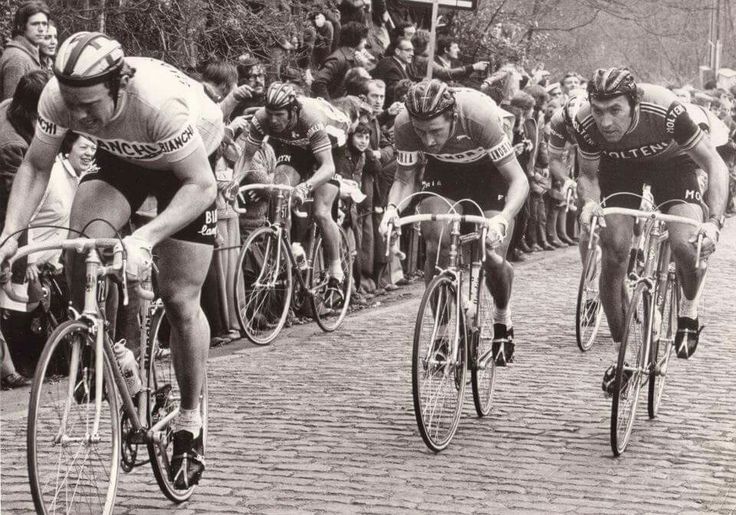

Last time up the Kemmelberg

They dropped down the other side, flew through Kemmel village, and they were on their way to Menen. They were going flat out, and the wind was blowing side on. I pulled everything out going down the Kemmelberg, made a big effort and quickly got back up to them. We were in the crosswinds, and it would have been the death to any hope of winning if I’d not made it back to the front just then. But when I got there it still wasn’t comfortable because they had one small echelon at the front, and the rest of us were in a line behind, gutter grovelling

.

I was in that line, crying out for a right or left turn so the wind wasn’t side on, so they’d swing out in front of me, bunch up a bit and let me in. There were some riders behind me, I kept looking behind me to check, but then it broke. Suddenly there was no one else behind at all. I was last man in the line and riding like I saw Guido Reybrouck doing, with my bike in a straight line but with me leaning over to get a bit of shelter from the guy in front. I was almost riding side saddle, with the bike in the wind but some of my upper body getting shelter.

But you can’t keep that up forever. At long last we changed direction, it bunched up and I was in. Phew! I looked around, there was 17 of us clear, so I started tapping through with everybody else. But the thing was I had some team mates with me, and that hadn’t happened very often at this stage of a Classic. I had Alain Santy and I had Raymond Poulidor, but we were up against the crème de la crème of Belgian cycling. Eddy Merckx, the world number one, Roger De Vlaeminck, Walter Planckaert, Eric Leman, Walter Godefroot, Frans Verbeek, Herman Van Springel and Freddy Maertens were all in that break.

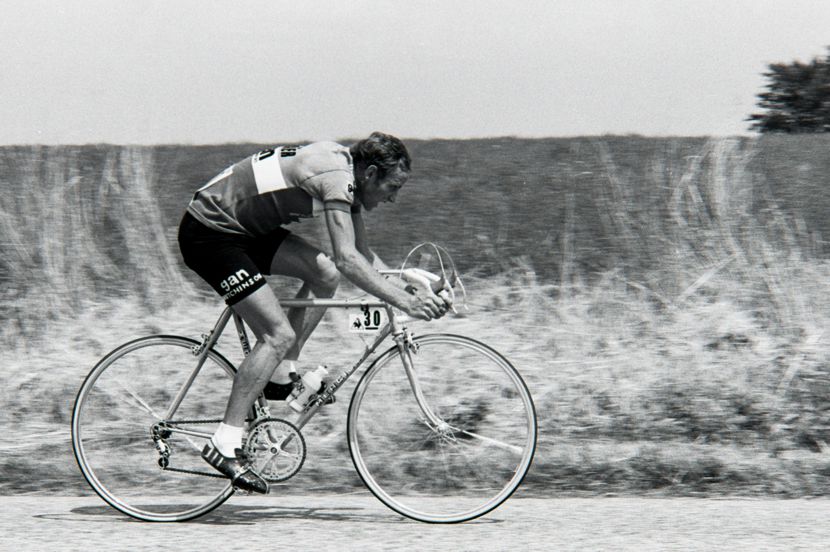

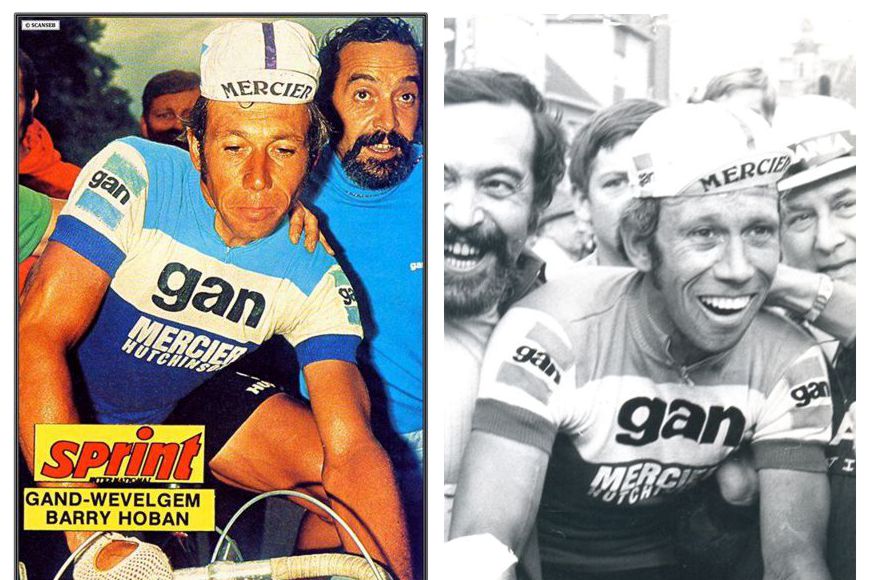

Hoban was already a formidable sprinter

We went through Menen, then through Wervik, and from there you had five kilometres dead straight to the line in Wevelgem. It has always finished in the same place, they re-draw the finish line each year. You can go down there now and see it. I knew I had overdrive that day, I knew I could win. On occasions I had it, Merckx probably had it most of the time, but now and again I had it, and the thing is you knew you had it, you knew you would win.

I was on the 14 sprocket and it was easy. I was just sussing the wheels, riding the train, and then the attacks started. Danguillaume attacked. Then Van Springel attacked. Gaps opened right left and centre, but I didn’t panic. Poulidor was there, so I was shouting; “Raymond, close the gap, close the gap,” and he closed the gaps. He did it once, twice, maybe three times, then Tino Tabak, I think it was Tabak, was the last to attack.

By then we had 300 metres left. It was the start of the sprint really, and Merckx, Leman and De Vlaeminck went straight up to Tabak, and they were all across the road in front of me, and I was praying for a gap to open, please let a gap open. Then 200 metres from the line they spread out a bit more, and a gap opened. I dropped it into the 13 sprocket, and wham, I went straight through the middle of them. And boy, that was my best-ever win, it was magnificent. I’d beaten the greatest of the Belgians, and you look on the line, it wasn’t by inches, I was a full length clear. And Eddy Merckx didn’t like it. He did not like it one bit.

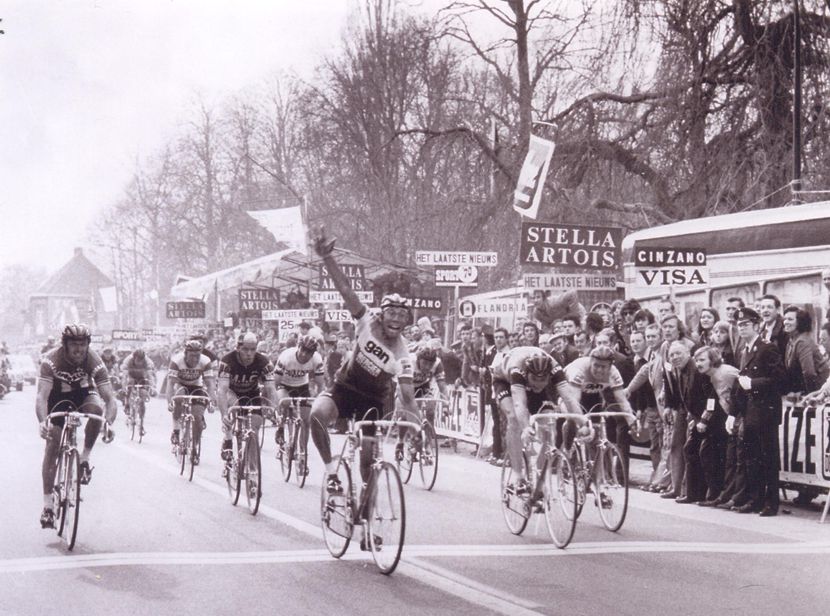

Hoban 1st, Eddy Merckx 2nd, Roger De Vlaeminck 3rd

There was a great photograph taken when Fred Debruyne was doing the post-race interviews, and there’s me there full of the joys of spring, and Eddy stood right next to me with a sour puss face on. The headline in the newspaper read; ‘Who won and who lost?’

I am so proud of winning that race. Ghent-Wevelgem was 244 kilometres long in 1974, and the average speed was 44.363kph. Tom Boonen won in 2012 at 42.450kph and it was 235 kilometres. And in 2014 John Degenkolb was the winner, doing just over 42kph for 220 kilometres. Now, I’m not saying it was me who made the pace that high, it was the collective class of the classics riders from that era, but I had to be there to sprint at the end. And when you think about what we did it on; steel bikes, 12 gears, no index gears, no lycra, no computers, and no radio…..No, we had to think for ourselves.

Hoban after winning in Wevelgem

Vas-y Barry, My cycling story by Barry Hoban is published by Cycling Legends.

Some readers' comments:-

"It's like being on the bike with Barry."

"An amazing account of what it was like to race against the likes of Jacques Anquetil, Eddy Merckx and Bernard Hinault."

"An honest record of a true pioneer of British cycling."

"After reading it I was left thinking just how famous Barry would have been if he raced today, and how much he would have earned."

You can buy it direct from this website using this link.