Why is Het Volk called Het Nieuwsblad?

A quick pirouette through some of the history of Omloop Het Nieuwsblad, the first cobbled classic of each cycling year.

Words: Cycling Legends

Photos: Legends Archive and Andy Jones

Photos: Legends Archive and Andy Jones

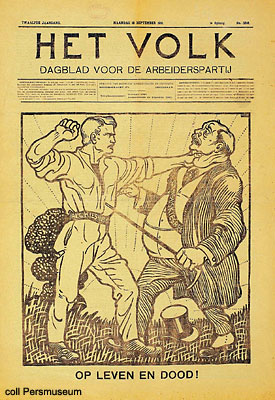

This first bit is complicated, and it mentions politics, but bear with us. Het Nieuwsblad, the race, is named after the leading Flemish language newspaper, which is politically conservative. So it is ironic that Het Nieuwsblad, the race, was founded by a newspaper called Het Volk, which was born out of the Christian Trade Union movement.

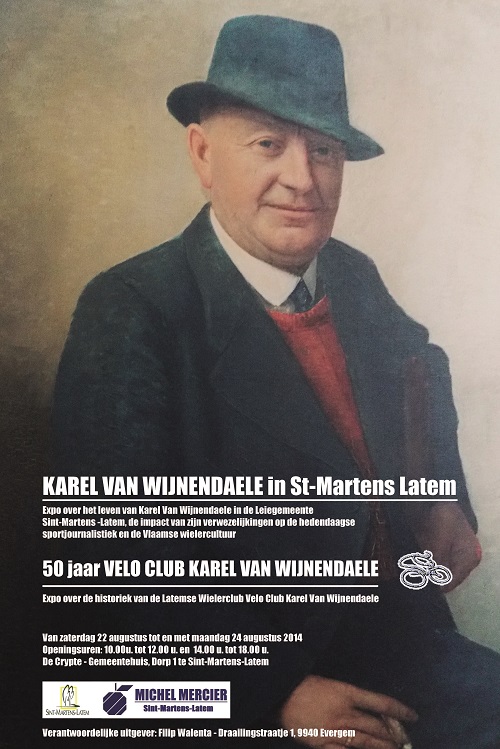

The Tour of Flanders is much older than Omloop Het Nieuwsblad. It was founded in 1913 by the first ever Flemish sports newspaper, Sportwereld. Sportwereld was edited by a former bike racer with a gift for words called Karel Van Wijnendaele.

Like many in the Flanders region of Belgium, Van Wijnendaele felt strongly about Flemish identity. He loved Flemish history and literature, and resented the attitude of Belgium’s French-speaking ruling classes, who tended to look down on Flanders, its language and the people living there. The Tour of Flanders, or Ronde van Vlaanderen to give it its Flemish name, was Van Wijnendaele’s vision, a challenging bike race with a route restricted to the historic County of Flanders, once a great trading power in Europe.

War troubles

The first Tour of Flanders was held in 1913 but it wasn’t run during the First World War. Then apart from 1940 it continued through the Second World War, because the occupying Nazis wanted to keep life normal, so long as the locals didn’t give them too much trouble. Unfortunately not giving too much trouble was seen by some as collaboration, and that came back to haunt the Tour of Flanders organisers when the hostilities were over.

The first Tour of Flanders was held in 1913 but it wasn’t run during the First World War. Then apart from 1940 it continued through the Second World War, because the occupying Nazis wanted to keep life normal, so long as the locals didn’t give them too much trouble. Unfortunately not giving too much trouble was seen by some as collaboration, and that came back to haunt the Tour of Flanders organisers when the hostilities were over.

Quite a few Flemish nationalists, whose aim was a free Flanders state, were accused of collaborating with the Germans, and Sportwereld was one of several newspapers taken over by the Belgian government. Several journalists were convicted of collaboration, and although Van Wijnendaele wasn’t convicted, he was banned from ever working as a journalist again.

But Van Wijnendaele wasn’t a collaborator. Love of cycling, and love of the race he’d grown from nothing was why he ran the Tour of Flanders through the War, and certainly not any sympathy for fascism. In fact Van Wijnendaele secretly worked for the allies, hiding downed British pilots inside his house. In response to being banned from the job he loved he sought support from the British authorities, and received it in the form of a letter from no less than Field Marshall Montgomery verifying Van Wijnendaele’s heroic acts. He was back in the game, but straight into another fight.

Sportwereld and the Tour of Flanders was taken over by the newspaper that runs the race today, Het Nieuwsblad. And when the post-war fallout settled, Van Wijnendaele was employed by Het Nieuwsblad to write about cycling and to run the race. But Het Nieuwsblad’s rival Flemish newspaper, Het Volk, which is Flemish for The People, started promoting sports events after the Second World War, and in 1945 Het Volk launched a new bike race for professionals called the Omloop van Vlaanderen.

That riled Het Nieuwsblad. Omloop and Ronde have similar meanings in Flemish, so Het Nieuwsblad protested to the Belgian Cycling Federation, which insisted that Het Volk change the name of its race to Omloop Het Volk. So another famous Flemish race was born, and now, since Het Nieuwsblad and Het Volk merged in 2009, what was Omloop Het Volk is now Omloop Het Nieuwsblad.

The Flying Milkman

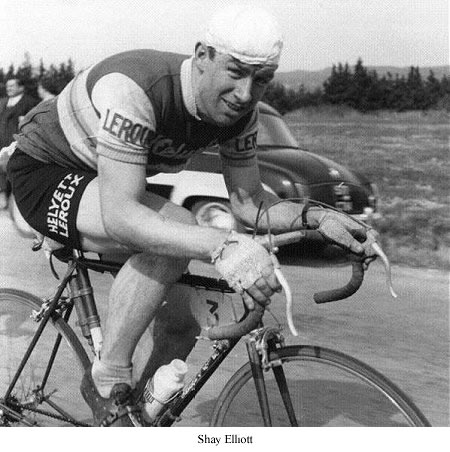

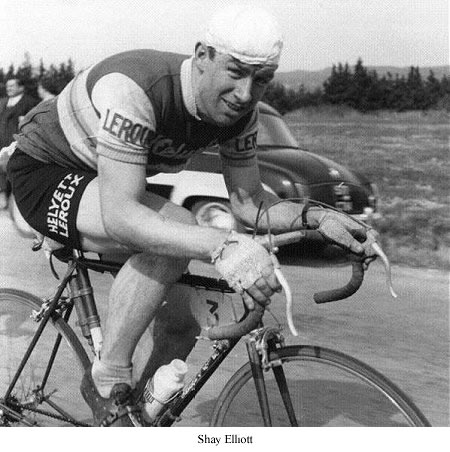

The race grew in importance throughout the 1950s. Then from 1957 to 1959 it linked with Ghent-Wevelgem to form the Flanders Trophy weekend, with Ghent-Wevelgem on the Saturday and Omloop Het Volk effectively becoming Wevelgem-Ghent on the Sunday. The Irish rider Shay Elliott won Het Volk the last time it was held in that format, he was also the first non-Belgian winner.

The race grew in importance throughout the 1950s. Then from 1957 to 1959 it linked with Ghent-Wevelgem to form the Flanders Trophy weekend, with Ghent-Wevelgem on the Saturday and Omloop Het Volk effectively becoming Wevelgem-Ghent on the Sunday. The Irish rider Shay Elliott won Het Volk the last time it was held in that format, he was also the first non-Belgian winner.

There have been many great victories, but Frans Verbeeck 's first stands out, if only because he was still a milkman when he won in 1970. It was at the start of Verbeeck’s second pro career, when he was a very different rider to the one he’d been during his first. Verbeeck first turned pro in 1963 for the Flemish Wiel’s-Groene Leeuw team. He won the 1963 season-closing Putte-Kapellen race in Belgium, then in 1964 he won a version of the Tour of Flanders restricted to first year professionals. After that Verbeeck started the 1964 Tour de France, and he did okay until stage nine, a 239-kilometre epic over the Bonette-Restefond, the highest paved road in France, which ended in Monaco. Jacques Anquetil won the stage, outsprinting Tom Simpson after seven and a half hour’s racing, but Verbeeck abandoned somewhere out on the road. It was too much suffering for the money he was making.

Sixties cycling was hard. The best, like Anquetil and Simpson, were paid very well, but riders had to win big races to earn big money. Nobody paid for potential. “I didn’t want my wife to get a job, but despite winning some races and doing well in others I wasn’t earning enough to support us, so in 1966 I stopped. I took over a milk delivery round, we expanded it and I forgot all about racing,” he says.

Verbeeck still followed the results though, and in 1967 he made an off-the-cuff remark about a race winner; “I was in my father’s bike shop, and I saw somebody I raced with had won a big race, so I just said, “Well if he can win that I could have won it.” But a guy in the shop overheard me. He was fan of mine when I raced so he said, “Well, why not do it then?” So I decided to race again, but I wasn’t going to give up work to do it.

“My father’s friend had a business that imported whisky, so he gave me a contract for six months from May 1968 and paid me 2500 Belgian francs per month (roughly £250). I still did my milk deliveries in the morning, and I trained in the afternoon, and I did okay. I did the same the following year, and I had six wins. I even delivered milk and cream to bakeries on the morning I won my first Het Volk in 1970,” he says.

Two in a row

Verbeeck gave up the milk round after that and started an almost manic training regime, one that saw him rest for just two weeks at the end of October, then start training up to eight hours a day, every day. He won Het Volk again in 1972 and many more races, even though he had to slug it out with the great Eddy Merckx. “My era was the easiest to race in, but the hardest to win. All the tactics you needed was to follow Merckx, but beating him was another question,” Verbeeck says.

Like Verbeeck, Merckx won Het Volk twice, as well as winning everything else, more often more than twice. In 1974 and 1975 Merckx’s super-domestique Joseph Bruyère won two in a row, setting a trend. Freddy Maertens won two Het Volks in succession in 1977 and 1978, then Alfons De Wolf (1982 and ’83), then Eddy Planckaert (1984 and ’85), then Wilfred Nelissen (1993 and ’94), and Peter Van Petegem in 1997 and ’98.

The first British winner of Omloop Het Nieuwsblad, remember the name changed in 2009, Ian Stannard did the double in 2014 and 2015. So did Greg Van Avermaet in 2016 and 2017, and if he wins again this year Van Avermaet will join the three-time winners Ernest Sterckx (1952, ’53 and ’56) Joseph Bruyère, who chalked up a third victory in 1980, and Peter Van Petegem, who added the 2002 race to his tally.

Sixties cycling was hard. The best, like Anquetil and Simpson, were paid very well, but riders had to win big races to earn big money. Nobody paid for potential. “I didn’t want my wife to get a job, but despite winning some races and doing well in others I wasn’t earning enough to support us, so in 1966 I stopped. I took over a milk delivery round, we expanded it and I forgot all about racing,” he says.

Verbeeck still followed the results though, and in 1967 he made an off-the-cuff remark about a race winner; “I was in my father’s bike shop, and I saw somebody I raced with had won a big race, so I just said, “Well if he can win that I could have won it.” But a guy in the shop overheard me. He was fan of mine when I raced so he said, “Well, why not do it then?” So I decided to race again, but I wasn’t going to give up work to do it.

“My father’s friend had a business that imported whisky, so he gave me a contract for six months from May 1968 and paid me 2500 Belgian francs per month (roughly £250). I still did my milk deliveries in the morning, and I trained in the afternoon, and I did okay. I did the same the following year, and I had six wins. I even delivered milk and cream to bakeries on the morning I won my first Het Volk in 1970,” he says.

Two in a row

Verbeeck gave up the milk round after that and started an almost manic training regime, one that saw him rest for just two weeks at the end of October, then start training up to eight hours a day, every day. He won Het Volk again in 1972 and many more races, even though he had to slug it out with the great Eddy Merckx. “My era was the easiest to race in, but the hardest to win. All the tactics you needed was to follow Merckx, but beating him was another question,” Verbeeck says.

Like Verbeeck, Merckx won Het Volk twice, as well as winning everything else, more often more than twice. In 1974 and 1975 Merckx’s super-domestique Joseph Bruyère won two in a row, setting a trend. Freddy Maertens won two Het Volks in succession in 1977 and 1978, then Alfons De Wolf (1982 and ’83), then Eddy Planckaert (1984 and ’85), then Wilfred Nelissen (1993 and ’94), and Peter Van Petegem in 1997 and ’98.

The first British winner of Omloop Het Nieuwsblad, remember the name changed in 2009, Ian Stannard did the double in 2014 and 2015. So did Greg Van Avermaet in 2016 and 2017, and if he wins again this year Van Avermaet will join the three-time winners Ernest Sterckx (1952, ’53 and ’56) Joseph Bruyère, who chalked up a third victory in 1980, and Peter Van Petegem, who added the 2002 race to his tally.