The Sprinter’s Classic

Paris-Tours is a classic, the fastest long-distance road race there is, here’s a look at its history and at the best two British performances in the race of the the Yellow Ribbon

Words: Chris Sidwells

Photos: Offside and Cycling Legends

The Yellow Ribbon, the Ruban Jaune was created in 1936, and is still awarded to the rider who wins a road race of 200 kilometres or more with the fastest average speed. Gustaf Daneels became the first holder of the Ruban Jaune when he won Paris-Tours in 1936 at an average speed of 41.45 kph. It set a precedent.

Of the 12 times the Ruban Jaune has been awarded, Paris-Tours was the race where the speed record was set on nine occasions. Amazingly, Paris-Roubaix has held it twice, and another old race once regarded as a classic, Paris-Brussels had it once. The current Ruban Jaune was set in 2015 when Matteo Trentin won Paris-Tours at the cracking pace of 49.641kph, that’s a fraction over 31 miles per hour.

Matteo Trentin winning in 2015

Paris-Tours is the sprinters classic, the fastest race over 200 kilometres on the planet. First held in 1896, when it was for amateurs only, it became a pro race in 1901. After that it only missed three editions through two world wars. Like most early races it was long, sometimes as much as 350 kilometres, and in early editions it was how well riders coped with the distance and rough roads that decided the winner.

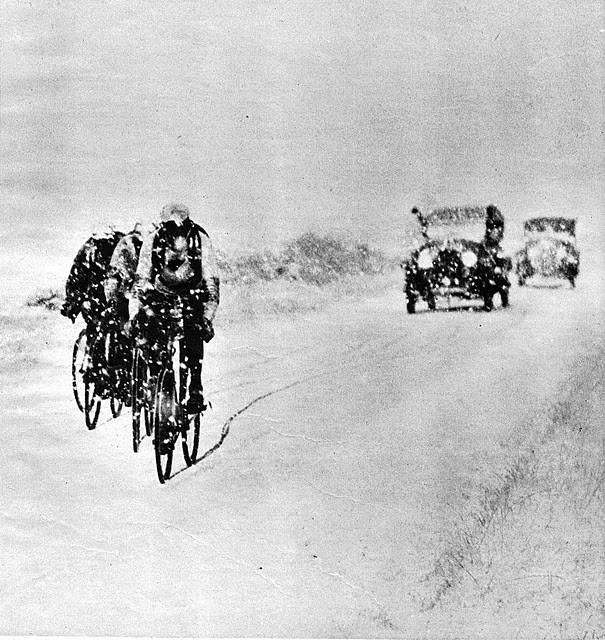

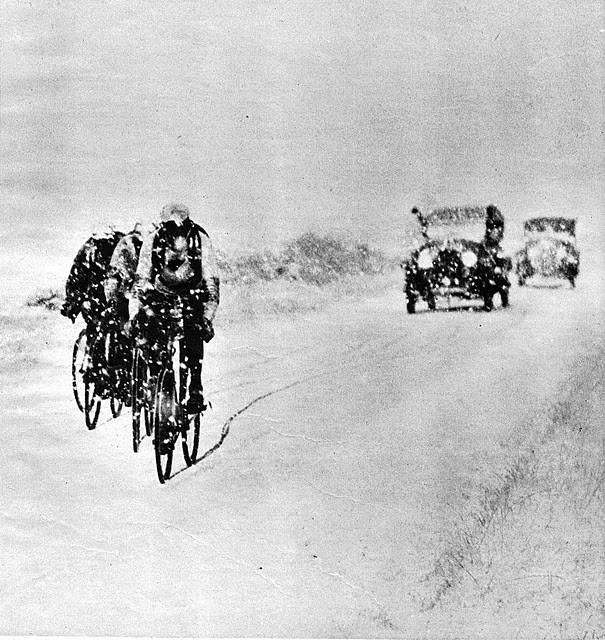

Then in 1911 Paris-Tours switched from September to the spring, when it was billed as the revenge race for Paris-Roubaix, which at the time was always held on Easter Sunday, giving rise to another name, La Pascale, for Paris-Roubaix. So if Easter was early difficult weather could hit Paris-Tours. The worst conditions were in 1921 when the riders had to battle through freezing cold and snow. Only eight made it to Tours, with Francis Pélissier the winner. But with time road conditions improved, the race distance was cut; and since the direct route to Tours is flat, Paris-Tours slowly earned its sprinters’ classic tag.

In 1951 it switched to early October and settled nicely into its autumn slot, and the fact that a sprinter won most years didn’t upset anybody very much, apart from cycling journalists and race organisers. Sprinters got a bad deal in the 1950s and ‘60s, they were regarded as a lower form of cycling life by the press, it was like sprinting was cheating.

Geography helped the sprinters. Tours straddles the River Loire, and the northern approach to the city, the way you arrive direct from Paris, is flat. However, just south of the Loire there are lots of short sharp hills, so in 1959 the organisers sent the riders through Tours, across the Loire, to complete four laps of a circuit in the suburb of Joué-les-Tours, which included the Cote de l’Alouette, and the race finished at the top of this stiff little hill.

The idea was to confound the sprinters, but in a wonderful irony the winner, Rik Van Looy was one of the fastest sprinters of his time. But Van Looy was a sprinter with a difference. He dropped the rest on the final climb, and was such an all-rounder that he won all five monuments and every classic during his career, even Eddy Merckx couldn’t do that.

Rik Van Looy

It’s the same with the two best British riders in this race, Tom Simpson and Barry Hoban. Both could sprint, Hoban won Tour de France stages in bunch finishes, but both were great all-rounders. Simpson won three out of the five monuments of cycling, and was Britain’s first elite world road race champion, while Barry Hoban won eight stages in the Tour de France and Ghent-Wevelgem. Simpson and Hoban both finished second in Paris-Tours, and no other British rider has done better since.

Hoban sprinting to another Tour de France stage win

Simpson was older than Hoban, so he featured first as runner up in 1963, the year he cemented his place in pro cycling as one of the best three riders in the world. Simpson was second in Ghent-Wevelgem and Paris-Brussels, third in the Tour of Flanders, and he won Bordeaux-Paris in 1963, all races that were part of the season-long Super Prestige Pernod competition, which served as the world rankings in those days. He had other top-tens in the classics and other counting races too.

Simpson didn't ride the 1963 Tour de France, concentrating on the world pro road race championships instead. He animated that race but came away without a medal. His good form continued into the autumn and he won the bunch sprint in Paris-Tours. Unfortunately the Dutchman Jo De Roo had slipped off the front in the final few kilometres, and did a fantastic job in holding off the rest in a race run off at record speed, over 27 miles per hour for 159 miles.

Words: Chris Sidwells

Photos: Offside and Cycling Legends

The Yellow Ribbon, the Ruban Jaune was created in 1936, and is still awarded to the rider who wins a road race of 200 kilometres or more with the fastest average speed. Gustaf Daneels became the first holder of the Ruban Jaune when he won Paris-Tours in 1936 at an average speed of 41.45 kph. It set a precedent.

Of the 12 times the Ruban Jaune has been awarded, Paris-Tours was the race where the speed record was set on nine occasions. Amazingly, Paris-Roubaix has held it twice, and another old race once regarded as a classic, Paris-Brussels had it once. The current Ruban Jaune was set in 2015 when Matteo Trentin won Paris-Tours at the cracking pace of 49.641kph, that’s a fraction over 31 miles per hour.

Matteo Trentin winning in 2015

Paris-Tours is the sprinters classic, the fastest race over 200 kilometres on the planet. First held in 1896, when it was for amateurs only, it became a pro race in 1901. After that it only missed three editions through two world wars. Like most early races it was long, sometimes as much as 350 kilometres, and in early editions it was how well riders coped with the distance and rough roads that decided the winner.

Then in 1911 Paris-Tours switched from September to the spring, when it was billed as the revenge race for Paris-Roubaix, which at the time was always held on Easter Sunday, giving rise to another name, La Pascale, for Paris-Roubaix. So if Easter was early difficult weather could hit Paris-Tours. The worst conditions were in 1921 when the riders had to battle through freezing cold and snow. Only eight made it to Tours, with Francis Pélissier the winner. But with time road conditions improved, the race distance was cut; and since the direct route to Tours is flat, Paris-Tours slowly earned its sprinters’ classic tag.

In 1951 it switched to early October and settled nicely into its autumn slot, and the fact that a sprinter won most years didn’t upset anybody very much, apart from cycling journalists and race organisers. Sprinters got a bad deal in the 1950s and ‘60s, they were regarded as a lower form of cycling life by the press, it was like sprinting was cheating.

Geography helped the sprinters. Tours straddles the River Loire, and the northern approach to the city, the way you arrive direct from Paris, is flat. However, just south of the Loire there are lots of short sharp hills, so in 1959 the organisers sent the riders through Tours, across the Loire, to complete four laps of a circuit in the suburb of Joué-les-Tours, which included the Cote de l’Alouette, and the race finished at the top of this stiff little hill.

The idea was to confound the sprinters, but in a wonderful irony the winner, Rik Van Looy was one of the fastest sprinters of his time. But Van Looy was a sprinter with a difference. He dropped the rest on the final climb, and was such an all-rounder that he won all five monuments and every classic during his career, even Eddy Merckx couldn’t do that.

Rik Van Looy

It’s the same with the two best British riders in this race, Tom Simpson and Barry Hoban. Both could sprint, Hoban won Tour de France stages in bunch finishes, but both were great all-rounders. Simpson won three out of the five monuments of cycling, and was Britain’s first elite world road race champion, while Barry Hoban won eight stages in the Tour de France and Ghent-Wevelgem. Simpson and Hoban both finished second in Paris-Tours, and no other British rider has done better since.

Hoban sprinting to another Tour de France stage win

Simpson was older than Hoban, so he featured first as runner up in 1963, the year he cemented his place in pro cycling as one of the best three riders in the world. Simpson was second in Ghent-Wevelgem and Paris-Brussels, third in the Tour of Flanders, and he won Bordeaux-Paris in 1963, all races that were part of the season-long Super Prestige Pernod competition, which served as the world rankings in those days. He had other top-tens in the classics and other counting races too.

Simpson didn't ride the 1963 Tour de France, concentrating on the world pro road race championships instead. He animated that race but came away without a medal. His good form continued into the autumn and he won the bunch sprint in Paris-Tours. Unfortunately the Dutchman Jo De Roo had slipped off the front in the final few kilometres, and did a fantastic job in holding off the rest in a race run off at record speed, over 27 miles per hour for 159 miles.

Simpson in 1963

A week later Simpson’s tenth place in Il Lombardia secured second overall in the Prestige Pernod rankings for him, Rik Van Looy was third. Simpson led the rankings going into the Tour de France but the Tour winner, Jacques Anquetil took over afater that. Still, Simpson was the world number two, the highest ranked British rider ever at that time, and not many have equalled it since.

A week later Simpson’s tenth place in Il Lombardia secured second overall in the Prestige Pernod rankings for him, Rik Van Looy was third. Simpson led the rankings going into the Tour de France but the Tour winner, Jacques Anquetil took over afater that. Still, Simpson was the world number two, the highest ranked British rider ever at that time, and not many have equalled it since.

Barry Hoban’s second place came in 1967, just over two and a half months after Simpson’s death in the Tour de France. It had been a tough year for Hoban in so many ways, Simpson’s death coming on top of Hoban suffering an abscess that required an operation and lengthy treatment, but he was getting back to top form by the end of the year.

“Paris-Tours started in Versailles, and I went through my normal ritual. I had this thing about going into meticulous detail, I didn’t want to be let down by a broken shoe lace or anything like that, anything I could control I did control. So I replaced my shoe laces, I made sure my bike had new white handlebar tape, and that it was in perfect working order. Then I used to look at myself and say, “Yes, shoes are perfect, ankle socks are spot on, the legs are nicely shaved, nicely tanned, nicely oiled.” Then I’d say; “Okay Bazza, the only thing that’s going to let you down is you, everything else is perfect.” I suppose it was a sort of mental rehearsal or visualization technique, a bit like things that sports psychologists get people doing today.

“We set off and there’s always skirmishes, and there was a skirmish going through the Vallee du Chevreuse before you get to the plains heading towards Tours. But eventually a group of us got away with about 17 riders in it. Rik Van Looy was there, Jean Stablinski was there, Walter Godefroot was there, all very good riders. So we ploughed on and that was that, the bunch was left for dead because none of Van Looy’s team would chase, none of Godefroot’s team would chase, and none of Stablinski’s would, and so on.

“Now, if you make a mistake in a race you must learn from it because if the average pro career is ten years; okay, mine was longer, one mistake means you’ve lost ten percent of your chances in that particular race. So, you make a mistake and you’d better learn from it. I made a mistake in the 1967 Paris-Tours, but boy I learned from it. I never made the same mistake again, and it changed the way I sprinted forever.

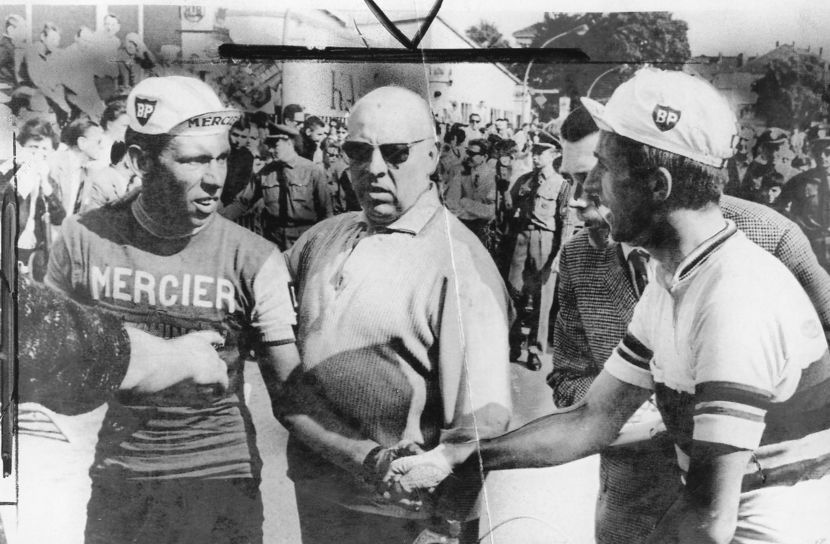

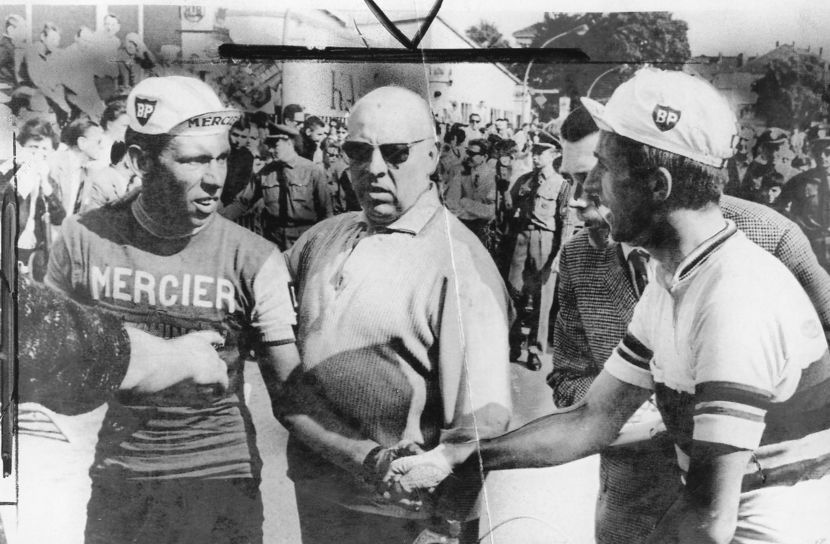

Hoban, left, and Simpson after Hoban's victory in the 1966 GP Frankfurt

“We were coming to the finish, coming along the side of the River Loire. You go down to one of the bridges, cross the bridge, then go up the other side of the river to the finish. I knew the guy to beat was Rik Van Looy. Van Looy was the greatest classics rider ever, the only one who has ever won every single classic. Merckx was great, super-Merckx, the Supremo, the best ever, but he never won Paris-Tours. Van Looy did, twice.

“Anyhow, we were coming along with five or six kilometres to go and I was right on Van Looy’s back wheel. But then he looked behind, saw me, and freewheeled. I thought; shit what’s he doing? And he’s still not pedaling, and suddenly there’s a ten-metre gap… then a 20-metre gap…. then a 50-metre gap. We’re losing. The race is going up the road and he’s losing and doing nothing about it, but I’m losing too. I thought, he must be a hell of a poker player. Then I chickened out.

“I accelerated, and as I did; bang, Van Looy latched onto my back wheel and stuck there. I went straight through to the front and into the sprint, with Van Looy still on my back wheel. And then I waited. I waited for Rik Van Looy to jump, and that was fatal. If you looked at Van Looy’s thighs, he had thighs thicker than my waist used to be, and when he jumped, wow, he took three lengths out of me in an instant. I went after him, and there was Godefroot there, there was Jose Samyn there, both good sprinters, but I flew past them. I came back at Van Looy all the way up the finishing straight; back, back, back. Then we flashed over the line and I was still half a wheel short. Fifteen metres more and I might have got him.

“So I was second, a good result, but I never sprinted that way again. I never let a sprinter jump first in any subsequent Tour de France or Classic finish. I always went first, then they had to get round me, if they could.”

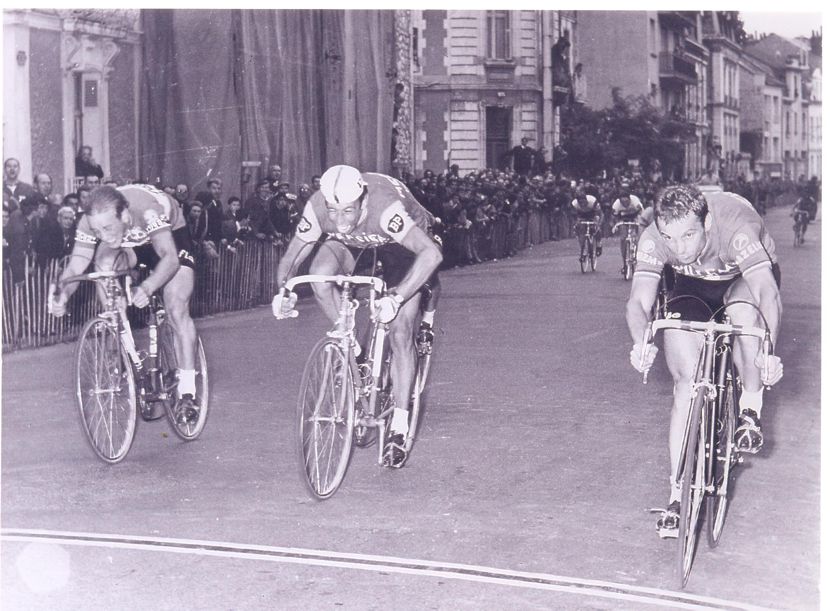

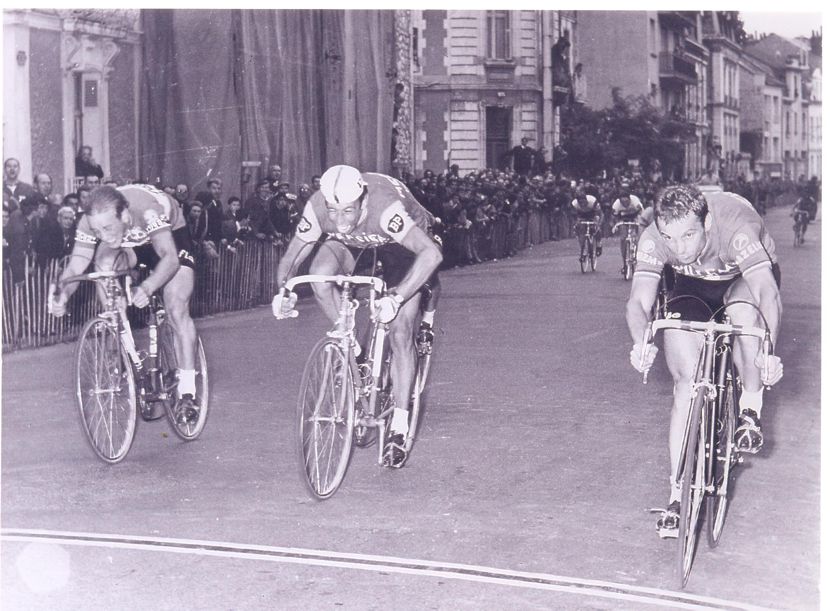

Hoban was just edged out by Rik Van Looy

So there it is, the best Brits in Paris-Tours. There are only two British in this year’s race, national champion Connor Swift and Alex Dowsett. Of the two Swift is a Yorkshireman like Hoban, and he takes part in the Tom Simpson Memorial ride each year. Yes, as omens go they’re pretty slim, but you never know, and Swift has had a sensational year.

“We set off and there’s always skirmishes, and there was a skirmish going through the Vallee du Chevreuse before you get to the plains heading towards Tours. But eventually a group of us got away with about 17 riders in it. Rik Van Looy was there, Jean Stablinski was there, Walter Godefroot was there, all very good riders. So we ploughed on and that was that, the bunch was left for dead because none of Van Looy’s team would chase, none of Godefroot’s team would chase, and none of Stablinski’s would, and so on.

“Now, if you make a mistake in a race you must learn from it because if the average pro career is ten years; okay, mine was longer, one mistake means you’ve lost ten percent of your chances in that particular race. So, you make a mistake and you’d better learn from it. I made a mistake in the 1967 Paris-Tours, but boy I learned from it. I never made the same mistake again, and it changed the way I sprinted forever.

Hoban, left, and Simpson after Hoban's victory in the 1966 GP Frankfurt

“We were coming to the finish, coming along the side of the River Loire. You go down to one of the bridges, cross the bridge, then go up the other side of the river to the finish. I knew the guy to beat was Rik Van Looy. Van Looy was the greatest classics rider ever, the only one who has ever won every single classic. Merckx was great, super-Merckx, the Supremo, the best ever, but he never won Paris-Tours. Van Looy did, twice.

“Anyhow, we were coming along with five or six kilometres to go and I was right on Van Looy’s back wheel. But then he looked behind, saw me, and freewheeled. I thought; shit what’s he doing? And he’s still not pedaling, and suddenly there’s a ten-metre gap… then a 20-metre gap…. then a 50-metre gap. We’re losing. The race is going up the road and he’s losing and doing nothing about it, but I’m losing too. I thought, he must be a hell of a poker player. Then I chickened out.

“I accelerated, and as I did; bang, Van Looy latched onto my back wheel and stuck there. I went straight through to the front and into the sprint, with Van Looy still on my back wheel. And then I waited. I waited for Rik Van Looy to jump, and that was fatal. If you looked at Van Looy’s thighs, he had thighs thicker than my waist used to be, and when he jumped, wow, he took three lengths out of me in an instant. I went after him, and there was Godefroot there, there was Jose Samyn there, both good sprinters, but I flew past them. I came back at Van Looy all the way up the finishing straight; back, back, back. Then we flashed over the line and I was still half a wheel short. Fifteen metres more and I might have got him.

“So I was second, a good result, but I never sprinted that way again. I never let a sprinter jump first in any subsequent Tour de France or Classic finish. I always went first, then they had to get round me, if they could.”

Hoban was just edged out by Rik Van Looy

So there it is, the best Brits in Paris-Tours. There are only two British in this year’s race, national champion Connor Swift and Alex Dowsett. Of the two Swift is a Yorkshireman like Hoban, and he takes part in the Tom Simpson Memorial ride each year. Yes, as omens go they’re pretty slim, but you never know, and Swift has had a sensational year.