Catching the Blue Train

This adapted extract from the book, Cycling Legends 01 Tom Simpson tells how Tom broke into top-level pro track racing and became the first British winner of a modern six-day.

Words: Chris Sidwells

Tom Simpson was a top international track rider, an Olympic bronze medallist in the team pursuit just three days after his 19th birthday and an exceptional Madison rider. Once he turned professional it was a natural step for him to use his track skill and speed to make extra money in the winter world of six-day racing.

Winning the Tour of Flanders at 23, being the first British yellow jersey in the Tour de France at 24 and gaining many other victories as well as high placings in other classics and stage races meant that by the end of 1962, his second full year as a pro rider, Simpson started getting contracts to ride winter six-day races. With his basic speed, added road strength and entertaining personality Simpson was a natural at this form of racing.

He found he could earn money too, but there was a big disparity between what riders like him earned when they started in six-days, even if they were classics winners and gained high placings in the sixes, and what the top riders earned. They were the ‘Blue Train’, the six to eight best and most established six-day riders of each generation who did every six-day on the calendar. They commanded the biggest fees, took the biggest cut of the prize and prime money, often worked togtether and even had a say in the make-up of the teams. Simpson had to be part of the Blue Train, and the rider to do it with was Ron Baensch, an uncompromising Aussie track sprinter with an intimidating presence. Baensch became Simpson’s ‘enforcer’.  Tom and Ron Baensch

Tom and Ron Baensch

The first time Ron and Tom raced together was in the 1963 Madrid Six-Day. For a track sprinter like Baensch the six-days were a good source of income, but until he rode with Simpson he says that he knew his place. He didn’t want to be part of the Blue Train, he just wanted to play his part in the races, earn enough money to continue his cycling adventure in Europe, and not upset anyone who might black-ball him for future contracts.

“Basically I was just a lazy bastard,” Ron recalled in an interview for Cycling Legends 01 Tom Simpson. “I was a sprinter, a natural talent. I’d ridden a few sixes before I got paired with Tom, and I could put on a show in the sprints, I could even beat Fritz Pfenninger, who was the fastest sprinter in the six-days when I started.

“Then Tom came along. Everyone thought he was just a road rider, but soon he was sprinting, even with the specialists. The crowd used to encourage him, the more they screamed the faster he went, drawing strength from them. I never knew anyone who could push themselves like Tom. He really thought that if he was hurting they were hurting too, and all he’d got to do was push a bit harder and he’d have them. It worked for him, but eventually it killed him.”

Ron paused for a moment to let that sink in, then continued, “Like I said, I could sprint in the sixes but I didn’t want to know about the long chases, that’s what we called the Madisons in those days. They were too hard for me. In the chases the big guys decided the race, I didn’t want to rock the boat. The sixes were all tied up in those days and I just wanted to go along with it. Then I got paired with Tom and his attitude just rubbed off on me. He wanted to win so much. All of a sudden I was racing for all I was worth in the Madisons.

“Tom wanted to take them all on, and he convinced me we could be the number one team in the six-days. He used to say, “We’re not having this, we’re not asking them if we can take a lap, we can be the best and then they will have to come to us to ask if they can win something.”

“And eventually we did it, we took them on, raced hard, even when they wanted to take it easy. I was fast, I could take half a lap, and soon Tom could do the same. He was a natural six-day racer, strong and so fast. We showed those arseholes, and they had to let us in. If Tom hadn’t died then in one maybe two years we’d have run the sixes.”

It took Baensch and Simpson a while break in though. As well as being tough and working together in races to keep the rest out, the Blue Train riders were very strong, very fast, and extremely skilful at this kind of racing. They knew just when and how to take a lap, and gaining laps is everything in six-day racing. They also knew when to back off, and when to keep it lit just enough so a team outside the Blue Train took ages to gain a lap, costing those riders a heavy physical toll to it. There are so many nuances in the six-days, so many skills it’s very hard to just batter everybody to win.

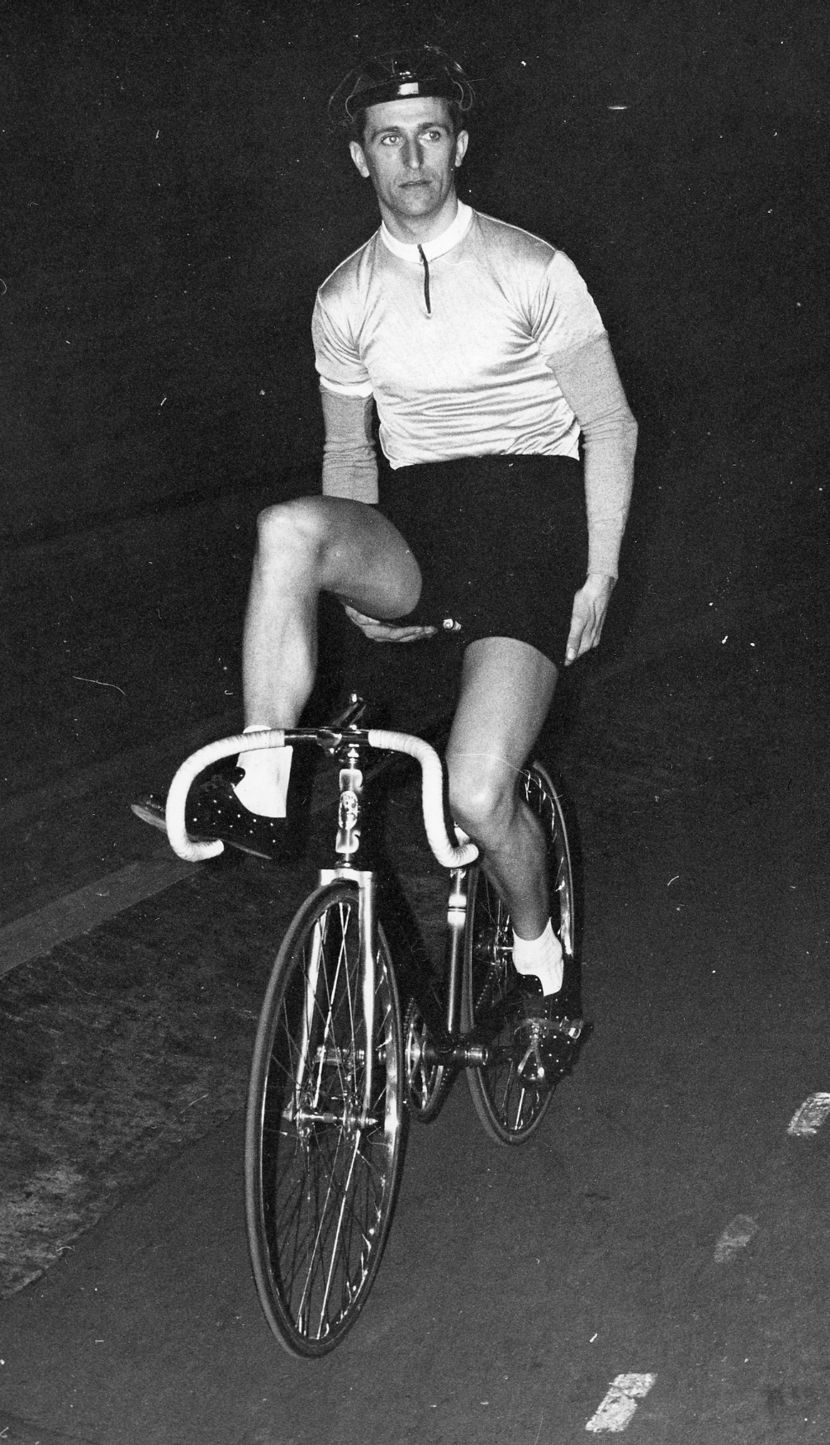

Baensch-Simpson finally took their seat on the Blue Train during the Zurich Six-Day in December 1964, and they took it by force. The first event on day-one was a one-hour scratch race for all the riders, any lost laps were combined when the riders joined to ride as two man teams for the rest of the race. The top riders rode very hard in this one to establish their superiority and the pecking order. It was brutal, but Tom and Ron came through it okay, no laps lost, whereas some riders were tired, even guys in the Blue Train. Tom grabs an easy moment during the 1964 Zurich Six-Day

Tom grabs an easy moment during the 1964 Zurich Six-Day

Next up was a series of sprints, and the local man Fritz Pfenninger, a big winner and part of the Blue Train, asked the Anglo-Australian pair to take it easy. They refused, and the response from the top riders was to rough them up a bit, but they stuck to it and won the sprint series. And that was them just starting, Tom and Ron kept the pressure on in every race, even continuing to race when the top guys wanted to call a truce.

By the end of that first day everybody was shattered, so Rik Van Steenbergen stepped in. He was past his best by 1964, but he’d been the best six-day rider of his generation, the King of the Sixes, and he still wielded power. He liked Baensch and Simpson, not only were they strong and fast, they were safe and they understood six-day racing. So sensing the time had come when Baensch-Simpson could hold their own physically, Van Steenbergen argued with the other Blue Train members that life would be a lot simpler and easier if they let Ron and Tom in.

It was the right decision, they were both popular with spectators. They both knew how to play to the crowd when they raced, and Tom was always up for entertaining pranks as well. Six-day fans loved him for that. In Zurich, for example, he rode a series of sprints with a long blond wig under his crash-hat. Unfortunately that bit of clowning backfired on him when the top riders decided to start a chase straight after the last sprint, and attacked. Tom was forced to ride the next hour-long Madison going flat-out and still wearing the wig, a bit of payback maybe? At the end of his last six-day that winter, in Milan, Tom said; “I’ve found that six-day riders are much more pleasant to work with than the road riders.”

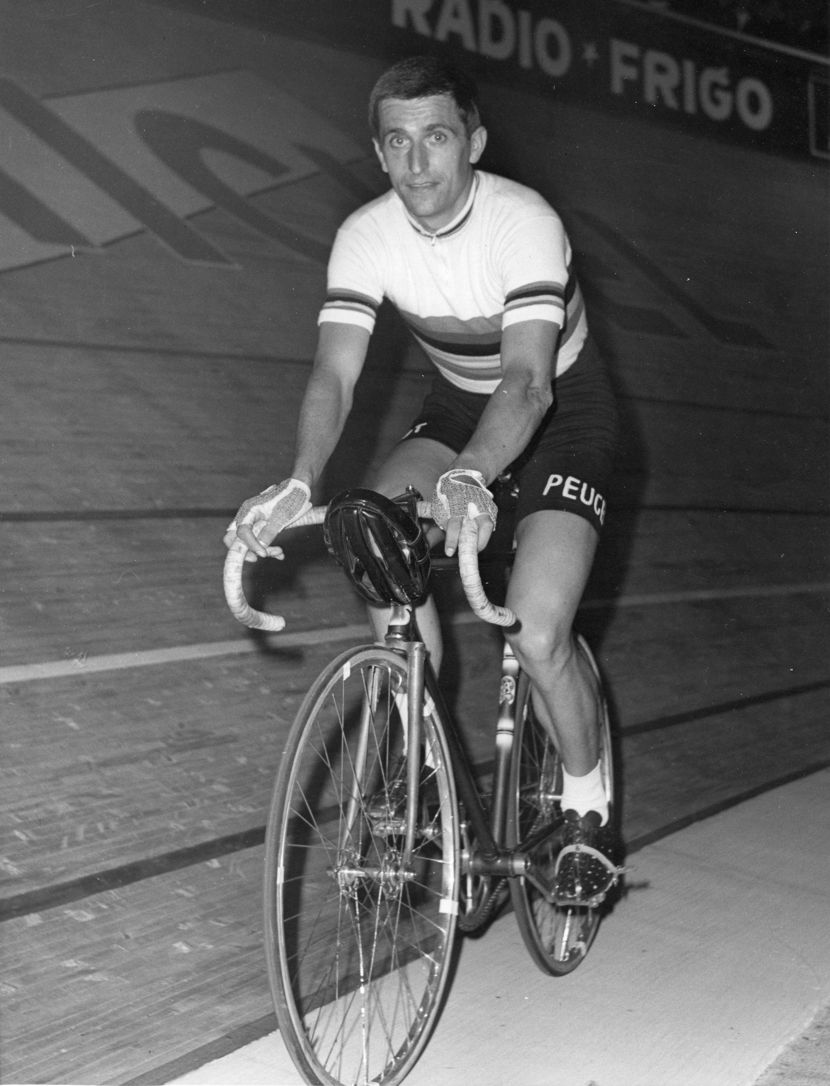

He like the six-days and planned to make them a big part of his future. In 1966, as reigning road race world champion, Tom told those close to him that he intended to focus on the road until he was 32, then concentrate on six-day racing. “That way I can have my holidays with the kids in summer,” he said.

Simpson’s six-day career continued its upward trajectory, mostly with Baensch as a partner, but in 1965, as road race world champion he was partnered with Peter Post, the man who took over from Rik Van Steenbergen as the King of the Sixes. With money and self-interest involved, Tom and Peter set aside their basic dislike of each other and made a formidable partnership. They won first time out, taking the Brussels Six-Day in early November 1965. That made Tom the first British winner of a modern six-day, and he was full of praise for his partner; “Peter was so strong, this was like a pedalling holiday,” he told Cycling magazine afterwards.

Brussels was a big track, which allowed some of the Madisons to be Derny-paced. Before the final hour-long Madison, Post and Simpson were in second place on the same lap as two new professionals; the super-strong Eddy Merckx and the super-fast Patrick Sercu. The young Belgians led because they had bigger points total gained in the non-Madison events, so the only way Post-Simpson could beat them was to gain a lap in the last hour.

They attacked from the start and made those final 60 minutes difficult for their rivals. At times Merckx struggled to hold his pacer, but when the Anglo-Dutch pair had almost gained the lap they needed to win, Tom crashed during a changeover.

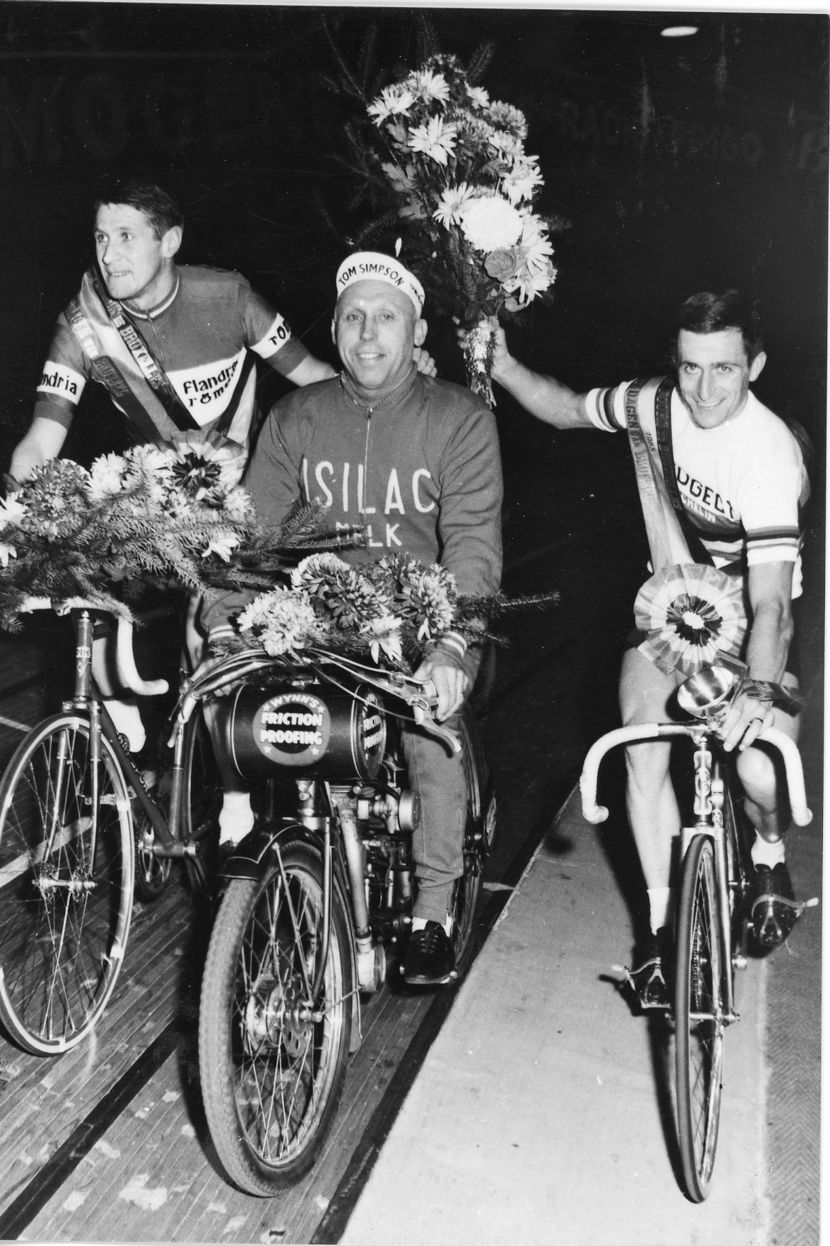

He wasn’t hurt and quickly resumed racing. Post had carried on pressing their advantage, and once back together, with just minutes of the race remaining, they gained a lap on Merckx-Sercu. Tom then rode straight over the top of the lined-out bunch, handed over to Post who couldn’t quite hold off Patrick Sercu, one of the fastest men ever to grace a six-day track. It was symbolic sprint win, though, because Post-Simpson were now one lap ahead and had won the Brussels Six-Day. Peter Post and Tom Simpson after winning the 1965 Brussels Six-Day.

Peter Post and Tom Simpson after winning the 1965 Brussels Six-Day.

To buy Cycling Legends 01 Tom Simpson click here.